Jordan Spieth’s blow-up at Augusta National was a vivid reminder of the importance of course management. Knowing the situation, and the number you need to shoot, can help golfers at any level succeed. Jack Nicklaus is generally regarded as the best course manager in the game. Tiger Woods famously didn’t hit a single driver the week of his 2006 Open Championship win at a sun-burnt, dried out Hoylake set-up.

Many of us practice it on weekends at our local courses. If we are two strokes up in a match against a lower handicap player coming to the last hole – say one guarded by water all along the left side – we will take great effort to keep the ball down the right side of the hole and just look for a way to make bogey and secure the match. It’s just common sense.

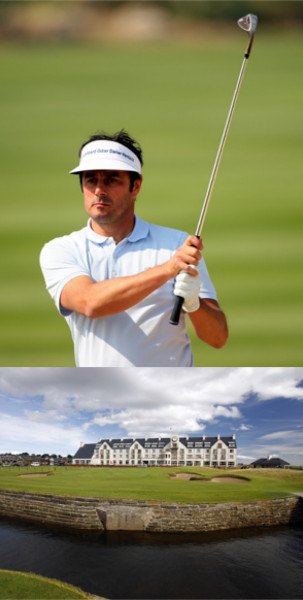

Sometimes though, for some reason, a golfer will lose sight of the safe path to victory. One of the most infamous course management hiccups of all time belonged to Frenchman Jean Claude Van de Velde at the 1999 Open Championship.

Van de Velde took a three-shot lead to the 72nd hole at Carnoustie. Carnoustie’s 18th hole is a par 4 with multiple water hazards that gobbles up poorly struck tee shots and out-of-bounds stakes all along the left side of the hole. With a three-shot lead, the prudent play was a long-iron lay-up off the tee, another lay-up and a wedge to attempt to make a working-man’s par 4, or a two-putt bogey. You can factor in a missed-green and still make bogey or double bogey the worst case scenario. The problem was Van De Velde had made birdie at the 18th in rounds two and three.

The golfing world collectively gulped that day when they saw the Frenchman call for the driver on the tee box. The BBC’s Peter Allis commented, “I’m not sure this is right.” He hit a wild tee shot that was fortunate to stay in the rough 10-15 feet short and right of the water. It seemed like mistake averted. Van de Velde could take a short iron and lay it up to 100 yards. Then he caught what seemed like a good break that turned into a bad one – his ball was sitting on top of the grass in the rough, giving him a perfect lie and the temptation to hit a more aggressive shot came into play. The Frenchman decided to hit a 2-iron with the hope of landing it right of the green, perhaps in a bunker to set-up a ho-hum bogey.

Instead, he pushed the long-iron way right and instead of staying close to the grandstand which is struck; the ball ricocheted back 30 or 40 so yards, hopping over the berm short of the green, into deep, unforgiving rough. Van de Velde then opted to try to carry his next shot over the small water hazard rather than playing out sideways to the fairway. “His golfing brain stopped about ten minutes ago, I think,” Allis commented. A combination of thick fescue and nerves produced a chunked shot that landed in the hazard. For a while, it looked as if Van de Velde would attempt to play it out of the hazard. After removing his shoes and socks and wading into the muck, he surveyed the situation and decided to take a penalty drop.

His next shot again came out to softly, perhaps protecting against the out-of-bounds stakes just left and long of the green. The pitch came to rest in the bunker. Van de Velde was now laying 5 in the bunker. He needed to hole the bunker shot for a 6 to win outright, or up and down for a 7 and the prospect of a 4-hole playoff. Van de Velde hit a decent bunker shot but still faced a 6-7 foot putt for triple bogey 7. He played his best shot of the hole dropping it in the center of the cup. Van de Velde wasn’t a factor in the play-off as Paul Lawrie won the Claret Jug after starting the day an incredible 10 shots off the lead.

The lesson of Van de Velde was hopefully seared into the memory banks of golfers all over the world. You have to understand and constantly keep in mind what the winning score is and how to think yourself through the final holes of a major championship when you have the lead.